Demographics : Intensify efforts in education and training

Today, in 2021, more than a quarter of the African population is of school age. By 2035, these young people will be on the job market. We must therefore invest today in the education of those who will have the continent in their hands tomorrow.

Because the effects of demographic trends only become apparent in the longer term, demographers and decision-makers sometimes struggle to persuade their fellow citizens of the need to mobilize resources today in order to benefit tomorrow’s society. African countries must intensify their investment in education and training, to help young people integrate into economic life and transition into the labour market.

This would allow African countries to benefit from their ‘demographic dividend’. Economists define this as the increase in productivity that occurs when the working population exceeds the dependent population, i.e., those too young or old to work. The demographic dividend therefore leads towards a ‘golden’ era in which children born during a baby boom have become adults, have fewer children than their elders, and are actively participating in the economy.

'Demographic dividend’ is a term used to describe an acceleration of economic growth resulting from a change in the age structure of a population.

A demographic transition that varies from region to region

Across Africa, the potential demand for basic education will continue to grow substantially over the next three decades. For example, the number of 6 to 15-year-olds, the demographic corresponding to compulsory basic education in Africa, will grow at an average annual rate of 1.8 per cent in the coming decade. This growth will then slow to 1.3 per cent between 2030 and 20501. Investment in education should at least be in proportion to this evolution.

However, these estimates hide important regional variations. Central and West Africa are expected to experience higher growth rates, while eastern, northern, and southern Africa are likely to experience lower rates because different regions are at different stages in their demographic transition. Consequently, west and central Africa will account for more than two-thirds of the continent’s school-age population in 2050.

The demographic transition is the transition from a traditional demographic pattern of high fertility and mortality rates to a pattern of low birth and death rates.

Sub-Saharan Africa at the centre of world population trends

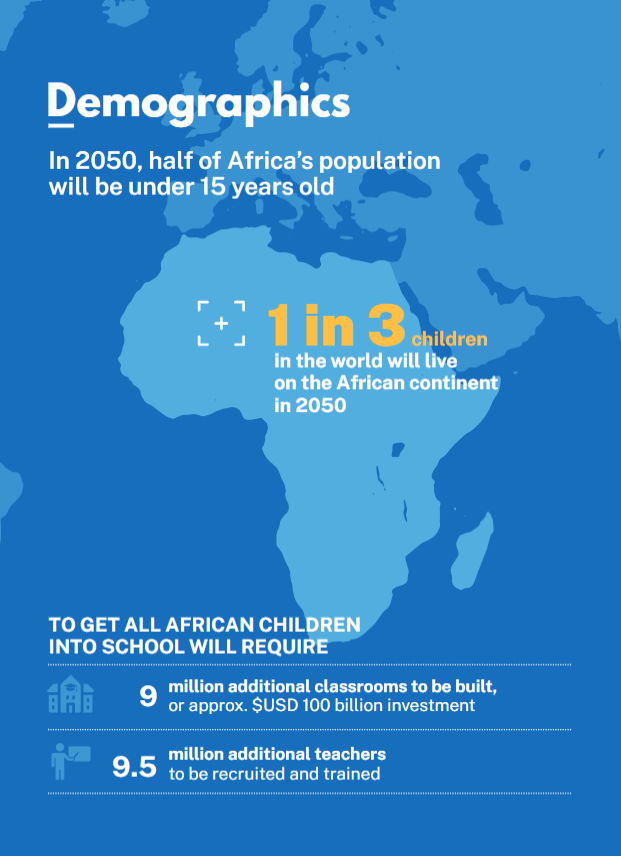

Whether the world achieves the international goal of universal schooling depends largely on the progress that is made on the continent. In 2050, one-third of children aged 6 to 15 will live in sub-Saharan Africa, compared to 1 in 5 today. Across the continent, demographic trends – and the needs they imply – vary significantly from country to country. At the two ends of the spectrum, Cabo Verde and Niger illustrate these differences well.

By 2050, the school-age population of Cabo Verde will fall by 19 per cent, while that of Niger will increase by more than 100 per cent – i.e., it will more than double – even though the proportion of school-age children in Cabo Verde is lower. This is because the demographic transition is more advanced in Cabo Verde than in Niger.In 2017, the pupil/teacher ratio in post-primary education was 35:1 in Niger compared to 16:1 in Cabo Verde. The secondary school completion rate was 17 per cent in Niger and 72 per cent in Cabo Verde in 2016. These differences in the dynamics of the school-age population result in greater pressure on resources in Niger than in Cabo Verde.

More than half of Africa’s population will live in urban areas by 2035

Urban population growth will undoubtedly be one of the continent’s major challenges in the coming decades. Demographers estimate that sub-Saharan Africa will have undergone its urban transition by 2035, by which time more than half of its population will be living in urban areas. While universal enrolment targets are far from being met in rural areas, the rapid urbanization of the continent makes it difficult to meet them in urban areas too, even though these are often considered more advantaged. Such fast-paced urbanization results in the development of informal settlements and shanty towns on the outskirts of cities, posing significant challenges as far as education is concerned. In some countries, access to education in these informal settlements is lower than in the surrounding villages. However, urban-rural inequalities persist, and educational needs remain greater in rural areas. While the share of the population living in rural areas is declining in relative terms, the school-age population in rural areas will continue to grow strongly in absolute terms. Another demographic characteristic of the continent is the young age of its population, raising the crucial issue of employability. Meeting this challenge will be essential if the continent is to reap the full benefits of the demographic dividend. Investing in skills development today is therefore the best way to prepare for tomorrow. These demographic issues and their implications in terms of investment in education and training are at the heart of the continent’s agenda. The theme chosen in 2017 at the African Union summit in Addis Ababa, Harnessing the demographic dividend through investments in youth, clearly raised this issue. A few months later, at its 72nd session, the United Nations General Assembly, in turn, launched the Demographic Dividend Roadmap for Africa. As we enter the decade leading up to the deadline for SDG 4, it is time for these political commitments to be translated into action, both at the regional and the national level.

(1) United Nations, Population Division, World Population Prospects, Revision 2019

Using demographics to clarify strategies and anticipate costs

In 2018, 207 million children were enrolled in schools in sub-Saharan Africa. While this number represents a high participation rate, the completion rates remain low: only 69 per cent completed primary school and only 44 per cent completed lower secondary school. Ensuring both access and success for all school-age children and adolescents by 2050 will require the construction of 9 million new classrooms and the training of 9.5 million additional teachers. Over the next decade, an additional US$19 billion will be needed. This additional expenditure represents 46 per cent of current spending on basic education.

Education: another source of social protection for health

On an individual level, a person’s likelihood of accessing information on good health practices increases with their level of education. A more educated person tends to be healthier in terms of nutritional balance and hygiene, and they are more likely to use health services. Similarly, at the intergenerational level, the higher the level of education of the parents – especially the mother – the better the care of the children is. These positive effects of education on health add up, helping to reduce the risks of morbidity and mortality. On the other hand, the COVID-19 pandemic shows that while the shape of the continent’s age pyramid gives it an advantage, the poorest and least educated populations remain the most vulnerable. Education, therefore, appears to offer further protection in terms of health and as a key instrument of resilience. Health, in turn, has positive effects on education. Good health and nutritional balance in childhood contribute to school success and well-being in adulthood. For UNESCO, the importance of the correlation between education and health is reflected in two of its priorities: providing safe, inclusive, and health-promoting learning environments and ‘comprehensive quality, sexual health education for all children and young people’.

Education and migration : getting all children into school

Strong urban growth is one of the two main demographic challenges in Africa. This phenomenon is largely fuelled by the arrival of young people from rural areas or from secondary towns and converge on the outskirts of large cities in areas with little or no infrastructure. Fertility is often higher in these urban areas because of population age and the low level of education. Thus, some African metropolises are faced with a paradox: the younger, school-aged members of the population are based on the outskirts of the city, with few schools, while the centre of cities with greater infrastructure are home to an aging population. A second major challenge concerns internally displaced persons, who migrate within their own country in search of safety. Linked to the increase in social and political conflicts and to growing insecurity, the number of internally displaced persons is on the rise in sub-Saharan Africa, particularly in the Sahel, where terrorist attacks are recurrent. At the end of 2019, Africa had more than 33 million refugees and internally displaced persons, representing 39 per cent of the total worldwide. Ensuring that the children and adolescents among these displaced populations are schooled is an enormous challenge, not only in financial terms, given the need for infrastructure and staff, but also in terms of psychological monitoring.

A financial simulation model for better planning : Focus on our action

IIEP-UNESCO Dakar, an institute specializing in educational planning, uses a set of technical instruments to help states to develop their educational plans and policies. Among these is the financial simulation model, which is essential for assessing the cost of implementing planning strategies that consider demographic factors. This projection tool makes it possible to anticipate medium- and long-term needs; for example, the number of teachers to be recruited at a given time for each level of education, which is based on the evolution of the school-age population. National goals can then be turned into quantifiable, sustainable, and credible action plans.