Financing: Innovating to maximize resources

Education accounts for the largest amount of public expenditure in Africa. However, its financing remains insufficient and ineffective. Finding ways to optimize public spending on education and to leverage additional resources and alternative financing tools is imperative if we are to guarantee high-quality schooling to the millions of children on the continent, especially the poorest.

Between 2000 and 2014, Africa experienced annual economic growth of 4 to 5 per cent (1), among the highest rates in the world. However, the cumulative effects of the COVID-19 pandemic, population growth, and the expansion of access to education are placing heavy demands on education systems.

Education in Africa: massive funding, but still not enough

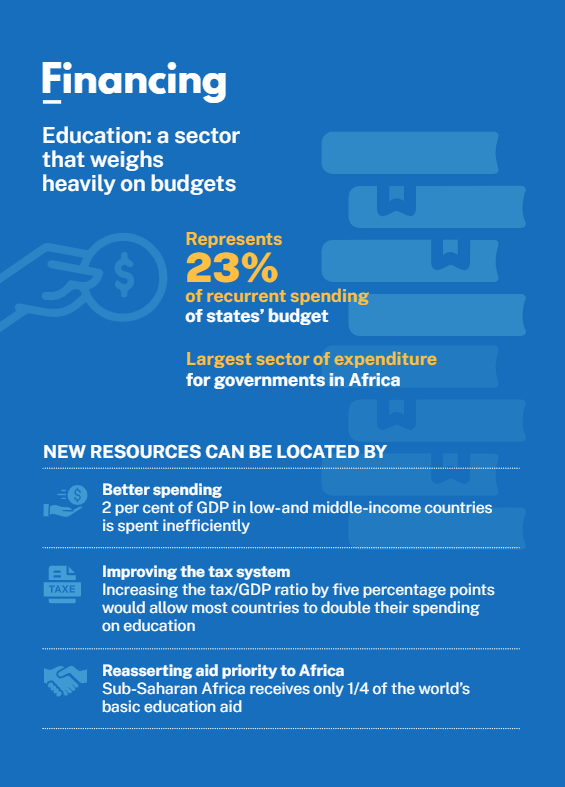

African governments allocated on average almost a quarter of their current expenditure to the education sector in 2015 (2), making education the largest single public expenditure item on the continent. Households are also heavily involved in financing education. In Africa, families contribute about 30 per cent of the total national expenditure on education, even though their means are extremely limited.

Despite the very high priority given to education by the state and households, the resources allocated to the sector on the continent are not sufficient to ensure high-quality education for all. As a proportion of domestic wealth, the resources available for education average about 4 per cent, whereas at least 6 per cent is needed to finance adequate education services.

Better spending: the primary driver for sustainable financing

Improving the financing of education is not just about increasing the sector’s budget. It is first about maximizing efficiency in the use of public education resources. In Guinea, for example, almost a third of the resources invested in primary education is ‘wasted’, largely because of children dropping out of school and/or repeating grades (3).

More efficient use of public funds is not only a means of optimizing educational outcomes, it is also a duty to taxpayers, and it sends a strong signal to funding partners. Ensuring greater transparency in how the education budget is spent, fighting corruption, and optimizing the governance mechanisms of education systems, are all powerful drivers for increasing national revenues.

There are also significant disparities in resource allocation in Africa. On average, the richest households capture 8.6 times more public resources for education than the poorest (4). Redirecting these resources toward the most disadvantaged would be a way to better distribute funds. On the continent, schooling difficulties particularly affect underdeveloped, rural areas with poor social infrastructures and a lack of teachers. Targeting these areas will help reduce social inequalities.

Alternative resources: building on private funding ...

Where can additional funding for education be found? All stakeholders agree on the need to involve the private sector more in the funding of education services. Financing tools exist, notably for vocational training and higher education. Through the development of public-private partnerships, companies participate in the financing of courses of study in line with the economic demand in countries, thus enabling them to meet their own labour needs. Some governments go further by creating regulatory mechanisms, such as introducing an apprenticeship tax for companies

.... and expanding the domestic resource base

Although African states allocate almost a quarter of their budget to education, the amount remains low in absolute terms because the countries’ own budgets are insufficient. Increasing the domestic resources of African states through economic growth and tax revenue is a key way of improving education financing. The International Commission on Financing Global Education Opportunity has estimated that 97 per cent of resources for education should ideally come from domestic resource mobilization (6). On average, low-income countries have a tax-to-GDP ratio of 17 per cent compared to 34 per cent for member countries of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) (7). According to the Global Partnership for Education, increasing this ratio by five percentage points would allow most countries to double their spending on education and other essential services over the next few years.