Inclusion : Ensuring equitable and universal access to education

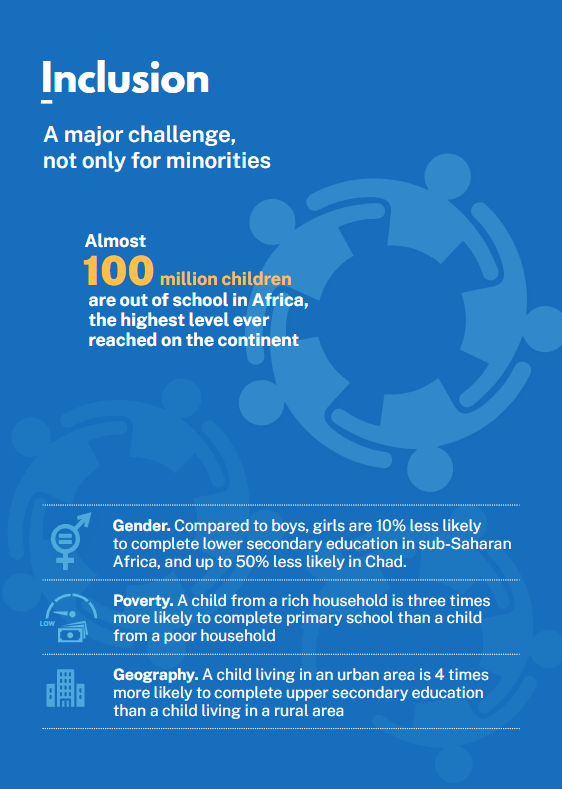

Family wealth, personal physical ability, and gender are major factors that determine children’s access to education. More than 97 million children are out of school in sub-Saharan Africa, which has one of the highest population growth rates in the world (1). The continent also has the highest exclusion rate for 6 to 11-year-olds. Access for all is both the cornerstone of inclusive education and a prerequisite for it.

The African continent accounts for 38 per cent of the world’s out-of-school children, up from 24 per cent in 2000. Only 7 out of 10 children complete primary school (2). This means that children excluded from basic education are not exclusively from disadvantaged areas, nor are they only from minority groups or groups with special needs. These out-of-school children, who represent a significant proportion of the region’s future generation, are currently being abandoned by the institution responsible for providing their schooling.

To establish inclusive education in sub-Saharan Africa, it is imperative to apply this fundamental principle: universal and equitable access to education.

The situation varies by country

Regional figures mask significant variations in the scale and pace of reform and the policy direction towards inclusive education. While some countries are succeeding in closing equity gaps through more inclusive education systems, others are falling behind. In Niger, for example, only 4 in 10 children completed primary education a decade ago, compared to 6 in 10 today. At the same time, Eritrea and Tanzania have seen their primary school completion rates fall drastically. Over the same period, Madagascar has significantly improved access to pre-school education, from 1 in 10 children in school to 4 in 10. In other countries, such as Burkina Faso or the Democratic Republic of Congo, the expansion of preschool education has been limited to a 2-percentage point increase over the same period (3).

Poverty, a major barrier to inclusive education

Beyond regional variations, children in sub-Saharan Africa are not simply excluded from the education system by sheer bad luck. This situation is often linked to several identifiable factors. Poverty remains without doubt one of the most significant barriers. In sub-Saharan Africa, children from the richest households are three times more likely to complete primary education than those from the poorest households (4). They are also 20 times more likely to complete upper secondary education. In recent years, many countries in the region have made a commitment to providing free secondary education. However, this measure only benefits children who have been able to complete primary education.

Effects of gender are variable and unpredictable

Across sub-Saharan Africa, there has been a gradual improvement in gender parity: 89 girls now complete lower secondary education for every 100 boys, compared to 84 girls a decade ago. However, this regional trend does not reflect the reality in many countries, where girls remain extremely disadvantaged. In Chad, for example, for every 100 boys, only 49 girls complete lower secondary education. Sometimes, however, disparities are to the detriment of boys. This is the case in Burundi and Senegal, where 83 boys graduate from secondary school for every 100 girls (5).

Place of residence, disability, insecurity: other aspects of exclusion

Where children live also has a significant impact on their access to education, often due to the lack of infrastructure in sub-Saharan Africa. Children living in urban areas are almost twice as likely as children living rurally to complete primary education and four times as likely to complete secondary education. Those with disabilities – including motor, visual, hearing, and cognitive impairments – are particularly vulnerable to exclusion. The vast majority either do not attend school or drop out early. Often, these barriers to education overlap and accumulate. In Mozambique, for example, almost half of men with disabilities can read and write, compared to 17 per cent of women with disabilities (6).

A boy from a disadvantaged background who lives in a rural area and does not speak the language of instruction has little chance of accessing education. His sister with a disability has practically none.

These challenges are compounded by insecurity and violence, as well as climate change, natural disasters, and epidemics (7). Sub-Saharan Africa has the largest number of internally displaced children in the world – 4.4 million – and their education is compromised by their situation (8). Refugee children are five times more likely to be out of school than other children (9).

The pandemic: an aggravating factor

In this already complicated context, the COVID-19 pandemic has resulted in nearly 300 million children in Africa missing school (10). The disruption has had a particularly negative impact on the most vulnerable students, for whom home-based learning is most difficult (11), owing to the absence, or inadequacy, of educational materials – not to mention the tens of millions of school-age children who cannot benefit from distance learning at all (12). As a result of the economic impact of the global health crisis, UNESCO estimates that 23.8 million children could be forced to drop out of school or be deprived of schooling by 2021. If the impact of the loss of learning is added, the total number of children who will not return to school because of the COVID-19 crisis is likely to be even higher. This potential ‘generational disaster’ (13) appears to be an additional barrier to inclusive education, which needs to be removed.

(1,2,3,4,5) Data from UNESCO Institute for Statistics.

(6) UNESCO, Report GEM, op. cit.

(7) UNESCO, Brief Education 2030, « L’éducation dans les situations d’urgence et les crises prolongées en Afrique subsaharienne », septembre 2016.

(8) UNESCO, Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre, ‘The impacts of internal displacement on education in Sub-Saharan Africa’, Working Document, 2020.

(9) Education cannot wait.

(10) UNESCO, ‘COVID-19: An unprecedented crash test for African education systems’, 2020.

(11) United Nations Sustainable Development Group, ‘Policy Brief: Education during COVID-19 and beyond’, August 2020.

(12). UNICEF, ‘COVID-19: Are children able to continue learning during school closures?’, August 2020.

(13) United Nations Sustainable Development Group, op. cit.

For an inclusive model of disability

Children with disabilities account for 15 per cent of the world’s out-of-school children (1). This figure is likely to be much higher in reality because such data are not collected in the majority of African states. The education gap between children with and without disabilities has been widening over the past two decades, both in terms of school completion and of learning outcomes. In schools, many children with disabilities are never identified. In Francophone Africa, only 5 per cent of second-graders participated in vision screenings in 2014 (2). To improve educational planning and increase the inclusion of these children in education systems, census methods must not only be strengthened but must also evolve.

How should we define whether a child is disabled? The prevailing approach continues to reflect a purely medical view of disability, to the detriment of a socially focused and humane consideration of the issue. To meet the individual support needs of disabled pupils, their environment and their ability to learn must also be taken into account. The lack of teacher training in inclusive education is also an obstacle. National legislative and policy frameworks reflect a growing political commitment to inclusive education in Africa, echoing the international framework on the right to education for young people with disabilities (3). The implementation – still too slow – of national commitments and initiatives is moving towards more equitable and inclusive education systems

(1) UNESCO, Report GEM, op. cit.

(2) World Bank, ‘Looking ahead: Visual impairment and school eye health programs’, 2019.

(3) Sustainable Development Goal 4, Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities

Empowering female teachers: a key driver of inclusive education

Gender inequalities are not just about access to education and student achievement. Worldwide, gender disparities persist in the teaching profession and, more broadly, in the administration of education systems. With only 43 per cent of teachers at the primary level being female, sub-Saharan Africa has the lowest percentage in the world. At the secondary level, this has declined slightly over the past 20 years. Female teachers represent only 30 per cent of the teaching force, compared to the world average of 54 per cent. They are also under-represented in scientific subjects. In Burkina Faso, for example, 20 per cent of teachers of languages and literature are women, compared to less than 10 per cent in mathematics and only 2 per cent in physics.

In addition to social and economic injustice, these gender imbalances in the teaching force have a negative impact on students’ perceptions and learning outcomes. A teacher of the same gender as the student may serve as a role model. He or she can play a central role in creating a climate of equality between girls and boys or, equally, can exacerbate discrimination in the classroom. Female teachers can provide safer learning environments for girls, reducing the risk of gender-based violence. While many studies exist in developed countries on the impact of the gender of teachers on students’ academic performance, research is more scarce in developing countries, particularly in Africa.

Advancing gender equality in and through education : Focus on our action

As technical lead of the Gender at the Centre Initiative, IIEP-UNESCO Dakar works to promote gender equality in and through education. Launched in 2019 during the G7 summit and coordinated by the United Nations Girls’ Education Initiative, this programme aims to strengthen the capabilities of eight sub-Saharan African countries to integrate gender issues into the development, implementation, and monitoring of education policies. With a team of gender-sensitive education planning and management specialists, IIEP-UNESCO Dakar supports governments, provides training, and produces and shares resources.