Participatory diagnostics: initial results in four countries

Following a methodology developed by IIEP-UNESCO Dakar, the members of each national team spend nine months identifying, dissecting, and analysing the professional practices likely to influence the quality of education in their country. This concerns not only the pedagogical practices of teaching staff in the classroom, but also the broader managerial and steering practices involving field actors at different levels of the education system: supervisors, inspectors, trainers, and other Ministry of Education staff at the central or decentralised level, etc. The aim of these diagnoses is always to go beyond what is officially recommended in national texts and policies, to understand what happens in practice in the field, and to gather the points of view of the main stakeholders.

While four African countries are currently carrying out their own participatory diagnoses, four other countries have already finalised this first stage, rich in insights: Burkina Faso , Madagascar , Niger and Sénégal.

Inspiring initiatives... that raise many questions

Many informal or isolated initiatives were identified by the national teams during this diagnostic phase, which often go unnoticed by the management of education systems. For example:

- In Senegal the diagnosis revealed unofficial in-service training partnerships between teaching staff. Locally, some schools organise ‘pedagogical discussions’ in the form of ‘tea-debates’ during breaks or even at weekends at the home of a colleague to compensate for the lack of pooling of teaching practices. "Faced with the challenge of improving the quality of education, these initiatives are relatively innovative and demonstrate a form of resilience on the part of actors in the field in the face of the realities they encounter," explains Moussa Hamani Ounteni, an expert in planning and institutional analysis at IIEP-UNESCO Dakar.

- In Burundi, the national team currently in charge of the diagnosis identified interesting initiatives by teachers to help pupils concentrate and memorise lessons learned in class. For example, after each teaching session one teacher systematically asks his pupils what they plan to say to their parents about what they learned at school today. To encourage autonomy in the classroom, other teachers encourage each pupil to keep a small personal notepad to write down the information he or she considers important to remember: rules, formulas, etc.

"What will you tell your parents when they ask you what you learned at school today?"

However, "officials tend to devalue this type of initiative when it is not officially prescribed by the authorities", observes Triphine Safari, Pedagogical Advisor at the Bureau d'études des curricula (BACPEF) in Burundi - and member of the country's national research team for the programme. While a few supervisors encourage these original practices (without capitalising on them), the others insist that they are not included in the teacher's guide - and may even verbally sanction these initiatives.

Valuing innovations: a common need in African education systems

At the classroom level and across the education system, great successes in education quality often come from small innovations. Yet these remarkable initiatives from the field need to receive the support and encouragement they deserve at different levels of the system. The question of how to support and steer innovations is therefore crucial.

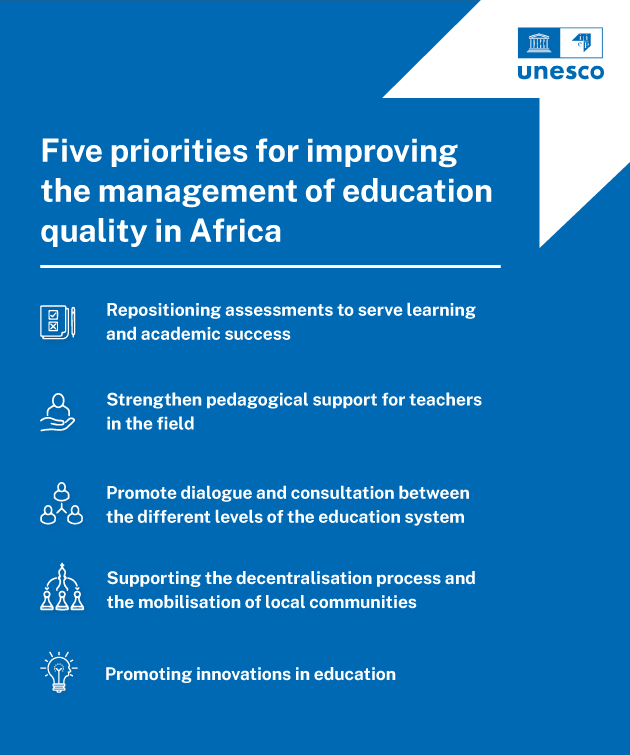

The first national diagnoses carried out within the framework of the ‘quality management’ programme have highlighted five converging themes in various countries. Promoting innovations from the field is clearly one of them.