Quality: Addressing the learning crisis

Despite years of strong and steady growth in school enrolment in sub-Saharan Africa (1), a learning crisis is threatening the future of entire generations. More than 8 out of 10 children do not reach minimum competency levels in reading and mathematics in the region. Why has the rapid expansion of education not been accompanied by high-quality learning for all, and what can be done about this?

Following the Convention on the Rights of the Child in 1989, the Dakar Declaration in 2000, and the Incheon Declaration in 2015, states and their partners have taken the right to education very seriously. Nearly 9 out of 10 primary school-age children are enrolled in school around the world (2). In sub-Saharan Africa, progress towards access to education has been particularly rapid and significant since the 2000s, even though tens of millions of children are still not in school. Despite schools filling up, there are signs that students are getting little benefit.

53 per cent of children in low- and middle-income countries have a learning deficit: they cannot read and understand simple text by the end of primary school. In poor countries, this rate can rise to over 80 per cent (3).

The learning deficit: a worrying trend

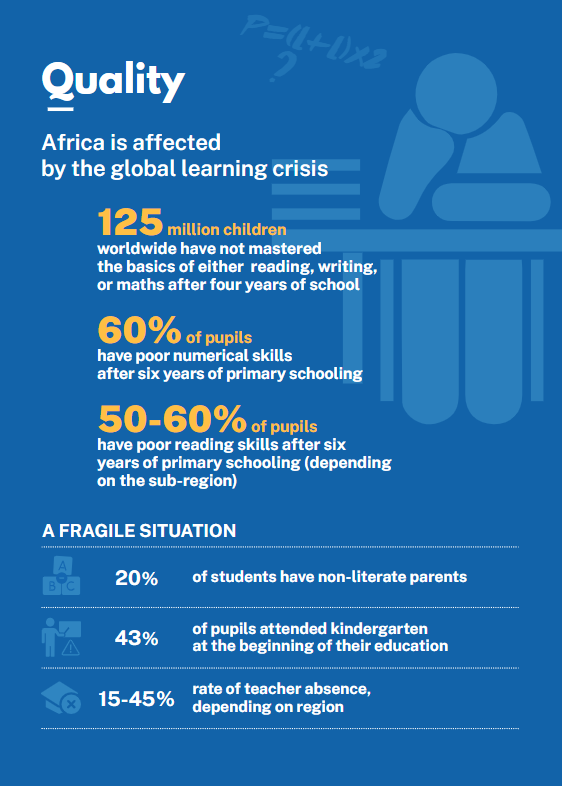

While 1 in 5 children and adolescents of primary and secondary school age live in sub-Saharan Africa, the region is home to a third of those who cannot read properly. After at least six years of primary schooling, about 60 per cent of pupils across the continent have inadequate numerical and literacy skills (4). If current trends continue, this crisis will affect an estimated 202 million children and adolescents. Many of them will have difficulty overcoming this initial learning handicap. Many will lose confidence in themselves. How did this happen? Will the growth in school access affect the quality of learning? Or is it just an accident, a growth crisis that stakeholders will soon be able to overcome?

Following a large influx of pupils, temporary solutions have become permanent

Education systems were not prepared for the rapid influx of students, which has been one of the main policy objectives for several decades, as shown by the quality of school construction or the diversification of teacher recruitment.

In terms of buildings, straw huts and other temporary structures have sprung up out of necessity, but without the minimum hygiene, comfort, and safety requirements. Similarly, many countries have had to hastily recruit young, unprepared teachers, who were parachuted into classrooms without any real pedagogical training and without permanent or stable contracts. Faced with a lack of teachers, parents have sometimes had to hire dedicated but unprepared community teachers themselves, often paying them in kind. These solutions are temporary and fragile, and not conducive to learning.

Local administrations also lack operational capacity and cannot maintain regular contact with schools and teachers. Nor can they increase the low level of funding for learning tools, books, and other materials. The quality of learning has deteriorated to the point where a learning crisis is now being reported by many stakeholders.

Beyond the lack of means, pedagogy is in question

Schools now host a new group of children, whose parents have not attended school and already have a lot to do, but teaching methods have not been sufficiently adapted to the local environment (language, culture, and so on). Learning topics are often disconnected from the children’s reality, and school calendars are not in line with community activities, such as agricultural seasons during which children often help their families. In other words, the standard school model has failed to adapt to the needs of new populations.

Yet governments and partners are not standing idly by in the face of this learning crisis. Many plans and projects are in place. Observing classroom practice has revealed the main difficulties encountered by teachers and the entire chain of supervision linked to the quality of learning. The lessons learned from these studies should make it possible to address issues of quality more effectively to review teacher training programmes and to help teachers adapt their methods.

Regular follow-ups: a key issue

Setting up or strengthening regular national learning assessment instruments is an absolute necessity, especially in the primary cycle. The objectives are to measure progress and to provide early warning if quality deteriorates. These tools can also inform educational managers and planners about the effectiveness of measures to restore the quality of learning. For example, to what extent have school results evolved following a reform of pedagogical approaches, an increase in book provision, or the implementation of an improvement programme in reading and maths? The results are often difficult to interpret but have the merit of focusing the attention of stakeholders on issues to do with quality.

Promising prospects

In addition to pedagogical management, administrative management – which is seen to play an important role in the quality of learning – is also the subject of studies based on new methodologies. IIEP-UNESCO Dakar is involved in this research. Are realistic and sustainable objectives set for the agents who will implement them? How do we guide teams through policy change? Systems should pay more attention to these key governance issues.

Other experiments exist in several countries, including Senegal and Cameroon, that have taken up the issue of national languages in initial learning. The government of Niger is studying the effects of tightening the curriculum for early grades around basic skills. Other initiatives are taking shape: the introduction of tools for systematically measuring time spent learning in school or the setting-up of distance learning networks for teachers. The COVID-19 crisis highlights the potential of these pedagogical perspectives.

This reflects a growing concern about the quality of learning in schools and appears to be an important turning point in the development agenda. However, there isn’t a magic or cheap solution to this crisis. Change in the next 10 or 15 years will require us to gradually build a new social and political consensus around education.

(1) UNESCO, ‘6 out of 10 children and adolescents are not learning a minimum in reading and math’,

(2) 017.2. Data from 2018 UNESCO Institute for Statistics.

(3) Data from UNESCO Institute for Statistics and World Bank, ‘New target: Cut learning poverty by at least half by 2030’, 2019.

(4) PASEC, ‘Quality of education systems in French-speaking sub-Saharan Africa: Performance and teaching-learning environment at primary level’ [in French], 2019.

Time for learning

In sub-Saharan Africa, teacher absence varies between 15 and 45 per cent (1). Even if the evidence remains scarce, their low presence in the classroom – due to ill-health, bad weather, or administrative problems – affects the quality of children’s learning and contributes to inequalities in school results (2). Delays to the start of school terms, strikes, and child absenteeism also have a significant impact on the time spent in classrooms. However, this remains a complex issue. What time are we talking about: the days when the school is open, the hours when the children are in the classroom, or the minutes when they are working attentively?

A school that appears to be doing its duty may, in fact, have its pupils doing very little work. Of course, it is difficult to set up reliable and permanent measurement mechanisms on a large scale. Such a system would be cumbersome and costly for administrators and might be rejected by teachers, who might feel they are being monitored. However, some methods to reduce the loss of learning time are emerging. By observing classroom activity, local governments can propose appropriate solutions. Central administrations have a key role to play in limiting delays in teacher deployment, managing career advancement, or changing salary perceptions. Replacing straw huts with more durable buildings would avoid losing weeks of school. Finally, based on how school days are distributed in the year and hours in the week, a more suitable schedule for the children could be developed.

(1) World Bank, 2017

(2) UNICEF, Time to teach: Teacher attendance and time on task in eastern and southern Africa, 2020

Learning to read, but to read what?

Many children are unsuccessful at school because they have not been able to master reading. The scarcity of books in schools offers one explanation for this. The number of textbooks does not always correspond to the number of children, which means that each pupil does not have their own textbook. Teachers [can] struggle to manage their distribution and use. Sometimes their content is confusing for the teacher or not suitable for classroom use. While useful to teachers and children alike, fiction and non-fiction books, dictionaries, and atlases are even rarer than textbooks.

As a result, the blackboard is sometimes the only medium for learning. The child copies as best he can, often without help. Their learning is therefore purely theoretical: they try to read but have nothing to read. Fortunately, there is hope. Very low-cost digital access to suitable materials is becoming widespread. In some countries, secondary school textbooks can already be downloaded free of charge via phone, thanks to activist initiatives. Private African publishers of children’s literature are also betting on low-cost digital access. Let us hope that most schools will seize these opportunities and will be able to make use of these new learning channels.

Transforming practices to improve the quality of education : Focus on our action

In response to the global learning crisis, IIEP-UNESCO Dakar, in collaboration with its partners (notably the Agence Française de Développement), is proposing a programme to support the management of education quality in Africa at basic level. It aims to support stakeholders at all levels of the education system to transform their professional practices in a sustainable way. The approach is based on participatory assessment and on the co-construction of coordinated and contextualized solutions. In parallel with the technical support missions, this innovative programme results in the production and sharing of knowledge and methodological resources that increase the quality of education