Winning the battle for youth employment

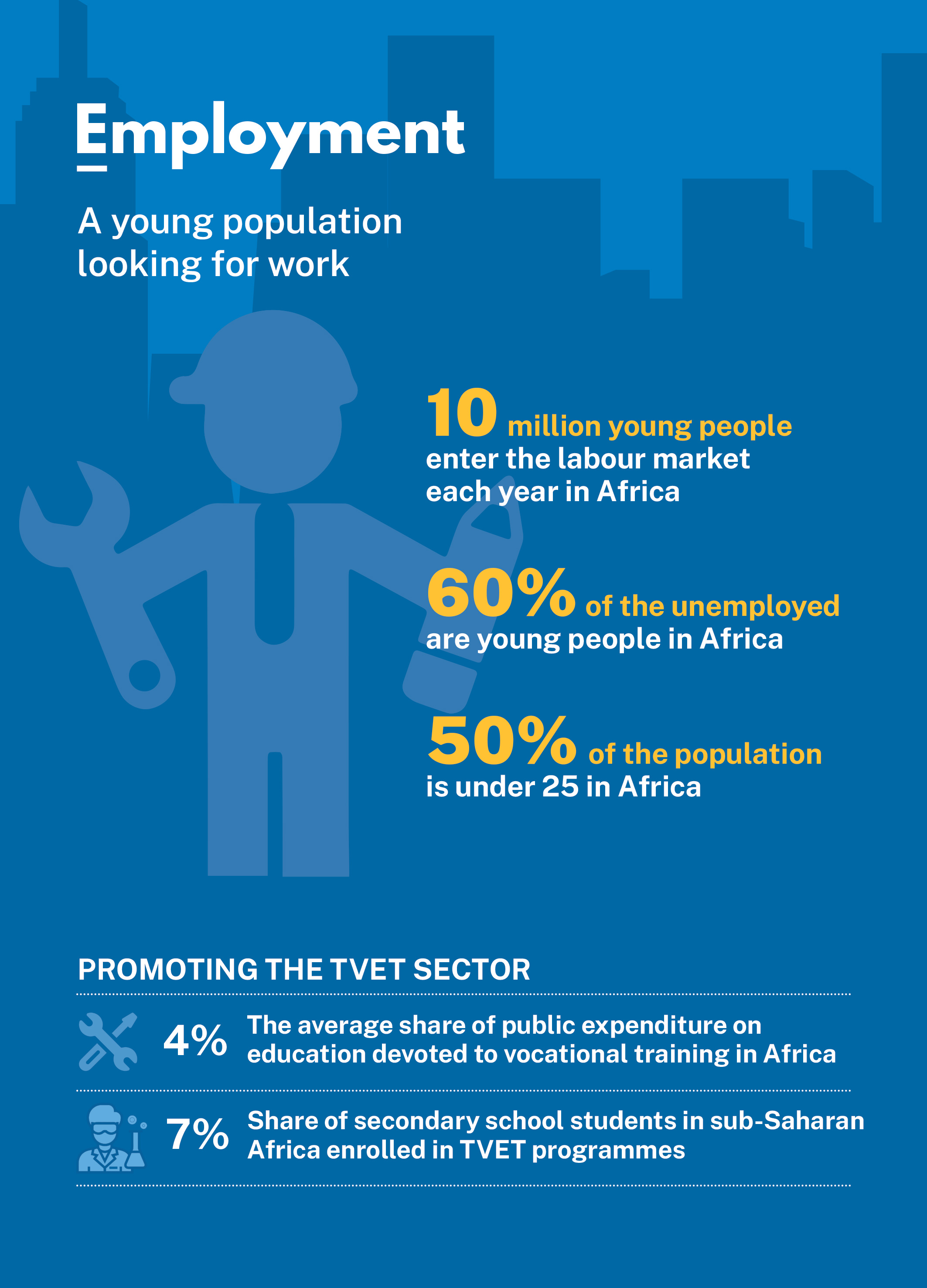

By 2030, about 100 million young people will have entered the labour market in Africa, representing more than 10 million young job-seekers each year (1). This demographic surge can be an opportunity if the continent can meet the employability challenge. Owing to a lack of appropriate skills, young people account for up to 60 per cent of Africa’s unemployed (2). To meet economic demand and build a future for young people, it has become urgent to strengthen the effectiveness of vocational training systems through partnerships.

While technical and vocational skill development is prominent in the United Nations’ Education 2030 Agenda, Africa’s technical and vocational education and training (TVET) systems are not yet up to the challenge.

Ensuring the training-to-work transition: a question of employability

While youth unemployment in Africa is alarmingly high, 1 in 3 of young Africans who are employed live in extreme poverty (3). The development of the African continent will depend on an increase in the qualifications of Africa’s young people and their acquisition of skills that meet economic and social demands. In sub-Saharan Africa, only 7 per cent of upper secondary school students were enrolled in TVET programmes in 2014(4). While this figure is lower than the corresponding figures for North America or Western Europe, the fact that there has been an increase indicates a growing interest in TVET on the continent. However, training programmes are often too general and do not necessarily meet the skill needs of countries. Technical colleges and high schools are often far removed from the professional world and do not give enough importance to practical work and placements. To ensure an effective and sustainable training-to-work transition, the focus should be on workplace training.

Strengthening monitoring and improving responsiveness

In the 2000s, many sub-Saharan African countries decided to place skill development at the centre of educational and social policies for development. National employment and training observatories have been created to gather statistics to improve information systems and assess the skill needs of economies. However, TVET systems are often rigid. They have difficulty adjusting to the rapid introduction of new training courses or abandoning courses with low demand from companies that therefore become irrelevant. Adopting a skills framework or a national qualifications system can help to strengthen the links between education, training, and employment, by identifying promising fields and anticipating the skills that should be given priority in order to boost particular economic sectors. These tools can be shared and adopted by several African countries, thus facilitating the mobility of learners and graduate workers through the mutual recognition of qualifications. These synergies and collaborative practices need to be further developed. Furthermore, the commitment of all stakeholders is essential to ensure that these schemes are implemented in a consistent and harmonious way.

Strengthening and accelerating partnerships

At the current rate, Africa will only be able to create 100 million jobs of the 450 million that are actually needed in the next 25 years. Generating new jobs requires relevant training courses to be designed upstream, in addition to sustained growth. To do this, greater involvement of economic stakeholders, particularly at local level, appears to be an essential means of leverage. Senegal has based its TVET modernization strategies on strengthening public–private partnerships to meet the needs of priority sectors such as construction and public works, fishing and agriculture. Thus, the Training Centre for Port Trades and Logistics (Centre de Formation aux Métiers Portuaires et à la Logistique) in Dakar was one of the first training centres in sub-Saharan Africa to provide a skills-based training approach.